Having a Cow: Raw Milk Enthusiasts Embrace Herd Shares

The green stuff may be legal in Colorado, but the white stuff…not a chance. I’m referring to raw milk, of course. Gluten may be the demonized “ingredient” du jour, but raw milk has long been the subject of controversy, conspiracy theory, and fanaticism.

Raw milk (for the purposes of this story, I’m referring to cows and goats—the two main dairy species in the U.S.) proponents claim it tastes better, is more digestible, higher in nutrients, and helps boost immunity. At least some of this is backed by science.

One of the reasons raw milk is so coveted is that many people with lactose intolerance (myself included) can often consume raw milk with no ill effects; goat’s milk is even more digestible because it has smaller fat cells than cow’s milk.

Studies show that at least sixty percent of adults are lactose intolerant (meaning they don’t produce lactase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down lactose, the main sugar in milk), which makes sense, since humans are the only mammals who continue to consume milk past infancy. Lactase isn’t present in raw milk, says Mark McAfee, CEO/founder of California’s Organic Pastures raw milk dairy, but it’s theorized that “the friendly bacteria in raw milk facilitate the creation of lactase in the [human] intestine, where it’s needed [for proper absorption].”

The term “raw” refers to milk that’s never been heated (not to be confused with pasteurization). Pasteurization is the process of heating milk to a specific temperature for a specific period of time, to inactivate or kill certain types of bacteria. It’s not fail-safe, however, as it doesn’t affect slow-growing microorganisms (more on that in a minute).

The raw milk controversy is due to it’s sale being regulated by government. Because it’s what the FDA considers an “inherently dangerous product,” many states prohibit the sale of raw milk. While nutritious and higher in protein, vitamins, and minerals (which are broken down by heat), contaminated raw milk can be extremely dangerous if consumed by pregnant women, infants and small children, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Listeria is the most common foodborne illness linked to raw milk and raw milk cheeses, followed by E. coli.

Hence, the FDA regulation. Many consumers are opposed to it, because they believe in freedom of food choice . Not to get too political about it, but they’re missing the point, which is to “protect those who have no voice,” to quote a Washington State food inspector I once interviewed regarding this topic.

As for why some dairy farmers choose to sell raw milk, it comes down to demand. Some small-scale farms find it hard to turn down the opportunity to sell such a coveted, profitable product, while others wish to sidestep the hassle and liability.

The legality of raw fluid milk is determined by individual states or counties, and while its sale is banned in Colorado, there’s a convenient—and legal—loophole that allows dairy farmers to supply consumers with raw milk. By selling a “share” of a cow or goat, the farmer can maintain his herd, and raw milk enthusiasts can get their fix.

With a herd share, the consumer essentially pays the farmer a fee for boarding “their” animal, in exchange for a regular supply of milk. Usually, members pick up their milk at the dairy, which provides an opportunity to form a relationship with your supplier and check out the operation for yourself (see footnote, below).

Whatever your reasons for seeking out raw milk, we’re fortunate to have a handful of excellent family farms in the Roaring and North Fork Valleys that offer herd shares. Carbondale’s Brook and Rose LeVan of Sustainable Settings keep a small herd of grassfed Guernsey cows for their share; Paonia’s Bella Farm, owned by Alison Klaus, has a handful of Brown Swiss cows, which produce exceptionally rich milk. Also in Paonia is Hava Farm LLC owned by Judson and Brianna Gurley, whose herd share features high butterfat Nubian goat milk.

To find a herd share in your area or learn more about raw milk, go to the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund website.

Note: When dealing with a product like raw milk, which under the wrong conditions doubles as a petri dish, it’s critical to know your farmer. Sanitation is everything with regard to dairy products, and every dairy farmer and cheesemaker I’ve met has told me that if a herd share won’t let you see their operation, you shouldn’t buy milk from them.

It’s also important to realize that it’s possible to get sick from pasteurized milk or cheese, although the media gives a false sense of security on this subject. At the end of the day, it all comes down to the herd management, handling and production practices at a given dairy or facility. When buying direct, be it from the dairy, farm stand or farmers’ market, caveat emptor. An ounce of research is worth thousands of dollars for a cure.

Ricotta

Recipe from The Paley’s Place Cookbook: Recipes and Stories from the Pacific Northwest (Ten Speed Press, 2008), by Vitaly and Kimberly Paley.

Makes approximately 10 ounces

- ½ cup heavy cream

- 4 cups whole milk (not ultrapasteurized)

- 2 tablespoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

- Pinch of kosher salt

1. In a nonreactive saucepan, combine the cream, milk and lemon juice. Cook over medium-low heat until the mixture reaches 205°. (Remember, cheesemaking is a science and temperature is crucial.)

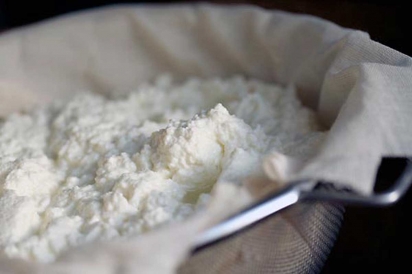

2. Remove the saucepan from heat and let the mixture rest for about 15 minutes. During this time, the curds and whey will separate.

3. Line a strainer with cheesecloth and set the strainer over a bowl. Ladle the curds into the strainer to drain the whey. Cover the strainer and bowl tightly with plastic wrap. Then refrigerate overnight to let the whey drain.

4. Discard the whey and wipe the bowl dry. Transfer the ricotta to the bowl. Stir in the salt, cover the cheese tightly and refrigerate until needed. Alternatively, you may transfer ricotta to an airtight container. Refrigerated, it will keep for up to 3 days.